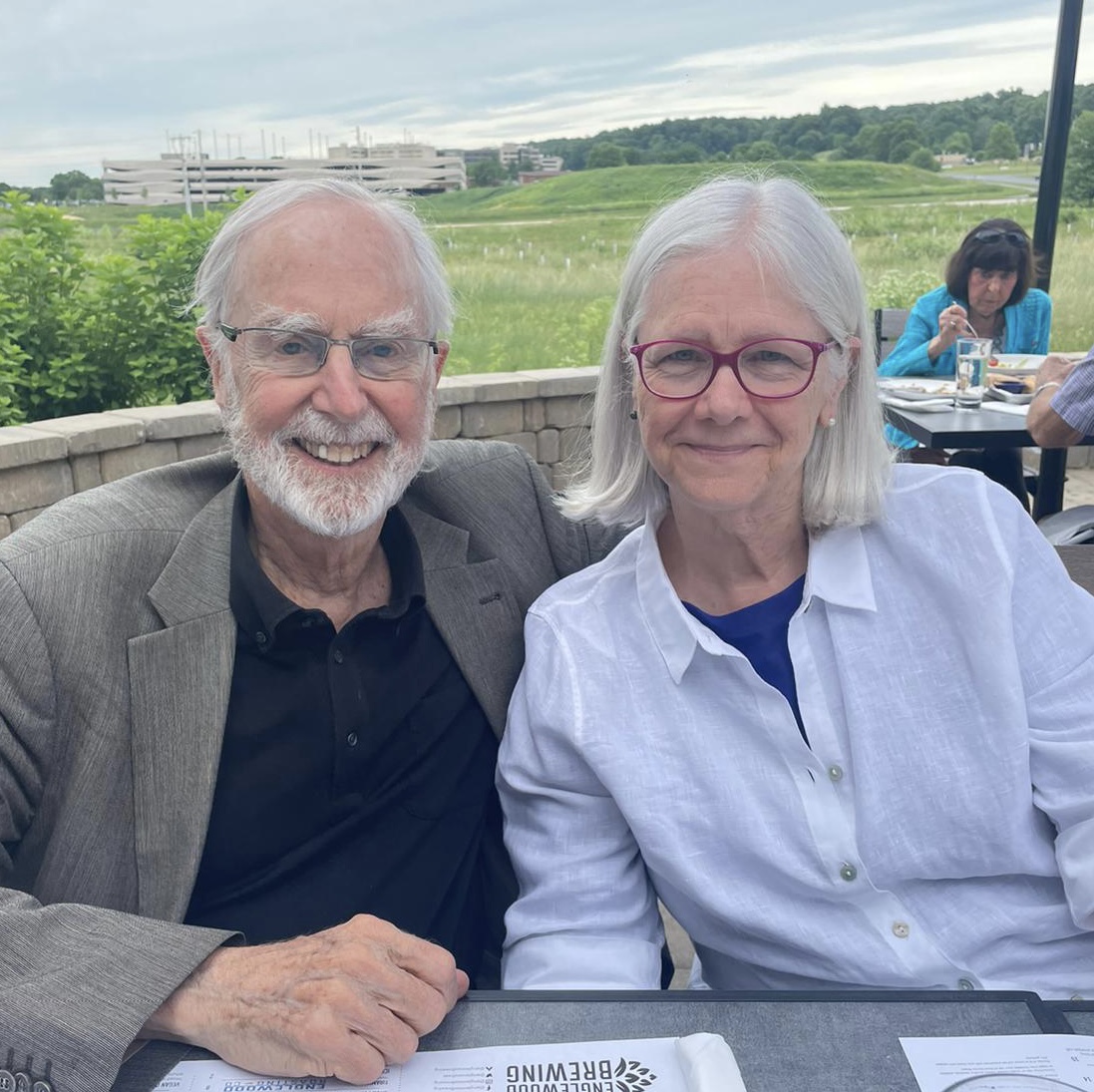

I have lived for 34 years in the grace of my husband’s love. It’s unconditional but it still took me a long time to count on it. I believe that my husband has always loved me – not always my actions, but always ME. I don’t have to change to have that love, but having that love makes me want to change, to do better, to be my best self.

My husband Dan was the first person I had ever known who loved me with all my faults. Not in spite of my them, not because of my them, but simply with them. Just as I am. Or as I was. As I have been over these many years, because during 34 years of living in the grace of that love I have been able to change and let go of patterns of behavior that don’t serve me or others.

That love stands as a mirror, reflecting back to me the best of me and because of that I have become a better person. I count on that love, never more than when I have not been my best self, and when I need the reassurance that I can find that best self again. The safe harbor of Dan’s love lets me love my worst self until I can find my best self. Or at least my better self.

Knowing that the harbor of that love is always there I am not as afraid to confront my darker side, to examine my faults fearlessly, to understand them and what triggers them. It’s the safety of that love that enables me to accept and grow away from my darker side. It holds space for me to be broken and to heal.

It took me a long time to see that God also loves me just as I am. I recently read of someone who was feeling burned out, oppressed by the weight of her work and the state of the world today. She decided to spend two days in a retreat and checked herself in to a retreat center, where she was assigned a spiritual advisor. She expected to be given exercises to do which would ensure her spiritual cleansing, her return to the light of the love of God. Instead, she was told to spend the two days living in the knowledge that God loves her now, apart from anything that she does.

This is how love has changed me. First, the knowledge of my husband’s love and then the knowledge of God’s love.

I now try to live each day in the knowledge of God’s love, in the knowledge that I don’t have to change to be worthy of that love. When I can do that, I am able to work to become the best version of me that is possible. Not to earn that love, but because of it.

The best analogy that I can find for this is being in a boat. Not knowing that I am loved is like having leaks in my boat. If the boat is leaky I have to spend all of my time bailing the boat out (ie, trying to be lovable), and have no ability to row or steer it. My boat is at the mercy of the environment around me. When I know that I am loved the boat loses its leaks and I can spend time rowing and steering it toward where I am meant to be.

We don’t have to change in order for God to love us. God loves us in order for us to change. Living in the knowledge of that love, with the foundation of that love, allows us to become our best selves.